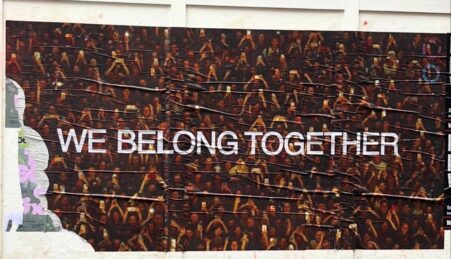

Featured image: Natasha Langman

In British culture, there is a tacit consensus that the only reason a person doesn’t drink is because there is something wrong with them. Either they’re a recovering alcoholic or they have strict parents who impose sobriety onto them – whatever the reason, alcohol is the one drug that if you don’t take it, people think you’re weird. I have lost count of the number of times I have told someone I don’t drink, only to be met with a mixture of confusion and anger. Or when I say to people that I don’t use social media, they look at me as if an extra head has just grown from my neck. And don’t get me started on all the lectures I’ve had to sit through, whenever I’ve told people that I don’t vote.

One thing that has always baffled me about other people is their willingness to conform. It still shocks me the tremendous effort people make in behaving in ways that please or copy others, rather than living the way they want. Though not always bad, the danger of conformity is that by imitating others you risk sacrificing your authentic self – and that way lies misery.

One can see this play out, for example, on social media. An online profile, rather than an accurate picture of a person’s life, is a highly edited digital persona designed to get the most likes and followers possible. Though some people use sites like Twitter/ X or Instagram for creative expression (think poets like Rupi Kaur), or to connect with others who share their passions, the vast majority do not. Instead, according to research, they post content tailored to suit algorithms, not necessarily content that reflects their real self. This is exacerbated by the prevalence of ‘echo-chambers’. Due to the nature of platform algorithms, users see content they already like and agree with, preventing them from seeing content that may cause them to question their beliefs or question the beliefs of those they follow. As a result, people are herded into online spaces where they are not challenged intellectually but instead repeat and regurgitate whatever opinions they encounter most frequently.

‘Cancel culture’ is another way that authenticity is stifled online. This refers to the witch-hunts and moral panics now commonplace, which begin with scouring a person’s accounts for ‘problematic’ posts and ends with their reputation being destroyed by online mobs. Sometimes, the shaming and hate-campaigns spill over into real life, with people making death threats to alleged wrongdoers or contacting employers to have them fired from their job. Anytime something is posted which is perceived to be ‘offensive’ or ‘problematic’ (whatever they mean), there are always legions of online activists and keyboard warriors ready to pounce. The situation is not helped by legislation such as the 2003 Communications Act, which is often used to prosecute people for posts they make online.

In the same way that the printing press and similar technology revolutionised our methods of communication, platforms like social media offer an unprecedented opportunity for the free exchange of ideas and culture. It is a shame that, instead of this, people use it to shame others for failing to adhere to ever more stringent expectations, or for repeating the evasions and half-lies of their preferred influencer-guru (think people like Andrew Tate).

By the nature of its algorithms, social media already encourages inauthenticity, but this is worsened by the constant threat of public denunciation and humiliation that is cancel culture. Whether online or offline, people self-censor and suppress anything which the crowd could smear as an act of bigotry. Rather than a platform for free discussion and authentic self-expression, social media has become in a way a prison of our own making.Hence, more than anything, I abstain from social media use because I have better things to do with my time than argue with people who want to police every word I say.

Leave a reply