By Megan Mcardle and Carla Acevedo-Ferron

“It was a photo that changed my life,” says Richard Davis at HOME café in the city centre. This picture is of Joy Division, taken by British photographer Kevin Cummins on Epping Walk Bridge in Hulme. The stark, steely images would go on to define the band and this part of the city’s legacy. It was also Richard’s introduction to Hulme and played a huge role in delineating his own creative career.

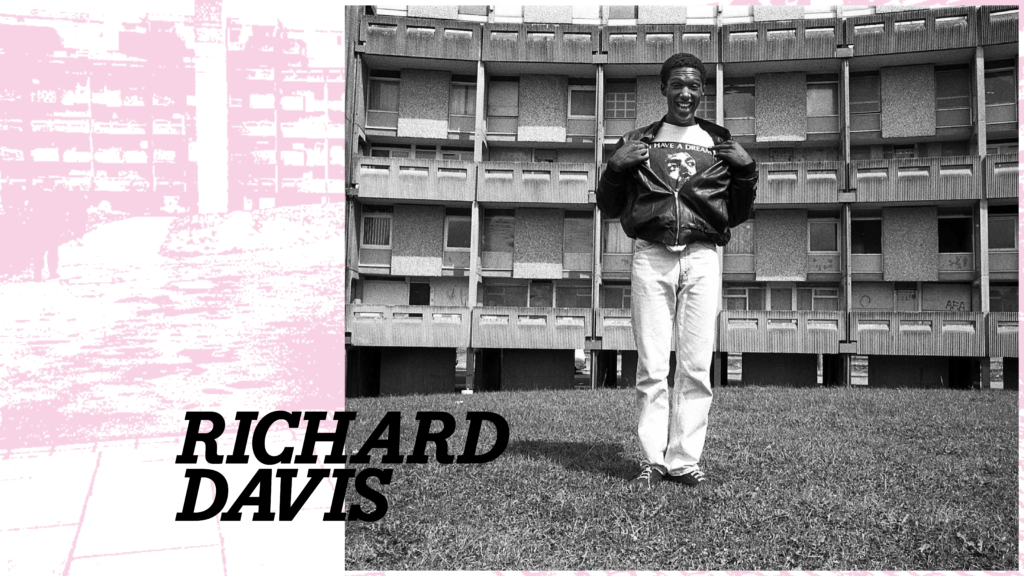

Born in 1965, the Manchester Met alumni’s story is a nod to how the city can shape us. Having walked the corridors of Manchester Polytechnic as a mature student, moving from Birmingham to the now Cavendish Halls, the photographer went on to capture the likes of Steve Coogan, Lemn Sissay and Caroline Aherne. His work encapsulates the vibrancy and rawness of Manchester in the 1980s.

In the 1970s, the community of Hulme was promised modern streets in the sky and a neighbourly utopia. Instead, corners were cut and the deck access ‘crescents’ were not fit for use. Tenants struggled with poor ventilation, lack of maintenance, social isolation and thriving pests — cockroach infestations were regular. The futuristic vision was an abject failure and just two years after opening, Manchester City Council deemed the development unfit for families following the tragic death of a five-year-old who fell from a balcony.

Those who stayed were segregated by shoddy design and blighted by rising crime rates. While others turned their backs on the Crescents, Richard stepped forward, viewing it as “otherworldly”. Describing Hulme as “a bloody good place to take pictures”, he arrived in the area as a 22-year-old student and would go on to build a studio and darkroom in his flat.

At the time, Richard was of the mindset he couldn’t be told what to do or how to think — an instinct he still carries with him today. Richard says you “saw life” in Hulme – then a creative hub full of artists, musicians and poets. In 1987 Richard was given the keys to a flat in the Crescents from a guy in a band that he met in a pub. The address, 257 Charles Barry Crescent, was on the back of all their records, and Richard was told he could live there rent-free as long as he forwarded the heaps of mail they received. This meant more of his money could go on photography, allowing him to immerse himself in the darkroom and completely devote himself to his craft.

Richard’s creative instincts blossomed in these surroundings, taking particular inspiration from Hulme’s graffiti scene. He describes how the art portrayed a unique blend of expression: “You not only had Northern graffiti, but also political graffiti and humorous graffiti. It was like no other place seemed to have that variation.”

During his time at university, Richard took advantage of every opportunity that crossed his path, including joining the university’s student magazine, PULP. He characterised this experience as “crucial”, adding: “It gave me so much access to people and meant early on I had an excuse to photograph people and things which led to many friendships. It was one of the best moves I made early on in Manchester.”

This connection opened doors for his craft, enabling him not only to develop his creative ambitions but also create meaningful relationships which have lasted a lifetime. Richard reminisces about his time as a student with “a lot of pride and enjoyment”. He says: “I loved every minute of it and have no regrets. I lived student life to the full and didn’t want to waste a single second.”

Reflecting on Manchester’s rapid transformation from his time as a student to how we experience it today, Richard raises questions about progress and property. He expresses a lot of empathy for today’s students embroiled in the housing crisis, asking: “Who’s all this new property for?” He worries developers are pricing young people out of the city, recognising that students have less room to try and fail, as money concerns can stifle creative freedom.

From Richard’s perspective, the essence of a captivating photo lies in one of three categories: portraits, buildings and graffiti. As an artist whose work has evolved over the years, Richard still has a preference for film over digital, emphasising film’s warmth, tones and connection to photographic history. “I’d say it’s like records. CDs are practical but they’re clean sounds. There’s a warmth to film: a life of its own. It’s not too sharp to focus, it’s not realistic sometimes. The great images aren’t always pinpoint sharp.”

Richard’s photographs of Nirvana act as a culmination of his approach. Before the band found fame, Richard photographed them at Manchester Polytechnic Student Union in 1989. The black-and-white image shows Kurt Cobain in a candid moment during the concert, capturing the vibrancy of the band. To Richard it was “just another gig at the time, nothing stood out”. He explains: “It was only with the release of [their second album] Nevermind two years later that things took off for them… If only we knew what was to come!”

These photographs became known as some of Richard’s best work, resurfacing in 2021 in the BBC Two documentary film When Nirvana Came to Britain. Richard struggles to pick out a favourite picture from his collection and has no plans to slow down: “I’m never happy with my photography; my next photo is always the best one.” This mindset comes from his time spent in Berlin in December 1989. The years from 1988 to 1990 taught him the importance of being busy; of always having a project, moving forwards and developing his style.

He shares a current project he is working on comparing the Barbican Estate in London with Park Hill in Sheffield, and the Hulme Crescents in Manchester: “Three estates, we’ve lost one. Two are now Grade II listed — could Hulme have been Grade II listed?” History influences a lot of Richard’s work; he discusses the way in which photographs document life, referencing moments in his life that have been documented, such as the miners’ strike in 1984-85 and civil rights movements. This pushed him to think about architecture and how we live our lives.

Richard considers what the future might hold, discussing how he is moving towards talking about photography, having recently given a talk at the Salutation Pub. He reflects on his life in Hulme, his football photography and the distinct identity of the “Manchester moment” he lived through. He explains: “It’s helpful for me to put all the pieces together in my life,” and this is something he wants to continue as he grows older.

As Manchester evolves, Richard’s lens continues to capture the city’s essence. He says: “The beautiful thing about Manchester is it’s a huge city culturally but actually physically quite small. You can get around it easily, get to know people easily and make friends easily. There’s a network here.”

These words serve as inspiration for students of today to take advantage of what the city has to offer. Like Richard did.

Pick up your copy of The LEGACY Issue on campus or read online.

Leave a reply