Humanity Hallows Issue 5 Out Now

Pick up your copy on campus or read online

By Bridget Taylor

As a result of recent events, women’s rights have been brought back onto the agenda in a big way. One particular scandal of Donald Trump’s election campaign that has seared itself onto the memories of feminists around the world, was the infamous “grab them by the pussy” remark, made in a conversation with TV host Billy Bush in 2005. Another memorable assertion during the campaign was Trump’s belief that abortion should be recriminalised and that any woman who then had an illegal abortion should be punished. This threat effectively came into being with Trump’s reintroduction of the ‘global gag’ rule, which bans any international NGO that receives US funding to provide abortion services, or even offer information about abortions. This will not dramatically affect the number of abortions taking place, but it will dramatically affect the number of women dying from unsafe abortions – tens of thousands every year.

A further worrying trend is the number of women in public life who are routinely abused online. This came to a head recently when MP for Hackney and Stoke Newington Diane Abbott spoke out for the first time about the racist and sexist abuse she receives on a daily basis. She commented that this ‘politics of personal destruction’ would have made her seriously reconsider entering political life if she had known about it when she became an MP in 1987.

These are serious issues. In recent months, the framework of the political debate has shifted rightwards. The media attention given to politicians like Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson in the referendum debate, and to Donald Trump’s campaign, has meant that racism, misogyny and xenophobia have all become a more legitimate part of public discourse. Consistently, the cry is that opposing this kind of abuse limits free speech, when in fact it is precisely this kind of abuse that silences free speech, that prevents women and ethnic minorities participating in this discourse.

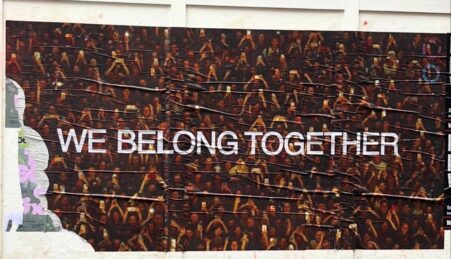

There is, and there will continue to be, resistance. Millions of women and their allies marched around the world on the day of Trump’s inauguration. The protests have sparked a ‘Stop Trump’ coalition in the UK and a series of planned marches throughout the spring and summer in the US. Feminism appears to be back on the agenda. But the past twenty-five years have seen a backlash against the aims and ideals of the feminist movement, and so the potential for progress to be made is fraught with difficulties.

You need look no further than a recent article in The Mancunion, ‘Reclaim the Night: We do not live in a rape culture’. In this article, the author contests statistics that state one in five women are sexually assaulted on college campuses in the US, and that only two per cent of rape allegations are false. His main line of attack seems to be questioning the ability of women to define for themselves whether they had been raped or not. A broader problem is the fact that The Mancunion felt this was an acceptable article to publish in the first place. Assuming that they did so ‘in the interests of balance’, this completely misses the fact that we live in an ‘unbalanced’ world, that society is skewed in favour of men and so their views are generally over-represented while women’s generally under-represented.

Another point of interest is that the author felt it was necessary to defend men who had been wrongly accused of rape, citing a case of a 17-year-old who hanged himself and ending the article by stating “not one second was reclaimed for him.” This was undoubtedly a tragedy, but here the author seems to miss a fundamental point about feminism and movements like ‘Reclaim the Night’ through his suggestion that men’s rights also need defending. The point is that feminism is also fighting for the rights of men. Patriarchal society confines both men and women into narrowly defined gender roles that oppress both. The high male suicide rate is a case in point. It is difficult for men to talk about their emotions or the fact that they can’t cope in a society that categorises such behaviour as ‘unmanly’.

By contrast, it was heartening to see that the Reclaim the Night march in Manchester last week was as well-attended as ever, made-up of marchers who seemed happy to define themselves as feminist. However, this made it difficult to get a sense of the current state of UK feminism from. As University of Manchester student Krutik Patel said, “Most of my male friends wouldn’t call themselves feminists. There’s a clear division by gender of people describing themselves as feminists in my life.”

Manchester Met student Wynne Taffinder feels that we are experiencing a feminist revival, “Even if feminism wasn’t in the zeitgeist at the time, it doesn’t mean that it wasn’t there.” She added, “There’s a lot more interest in social justice generally,” before going on to stress that it’s important to combat the “alt-right movement who are really keen to point the finger at feminists for being the epitome of evil.” Wynne also noted the scale of the problem facing any kind of movement: “It’s hard to boil feminism down into a handful of things to fix… you need a culture shift and that’s really hard to bring about.”

And although the importance of a feeling of solidarity and empowerment can’t be emphasised enough, it is hard to say how the march helps to bring about that culture shift, when it does not feel like it’s part of a more sustained movement. Wynne emphasised that feminism comes in many forms and it’s not all about protesting: “Reclaim the Night matters, but at the same time if you find it a really compelling cause then it’s worth exploring other things as well. Activism isn’t for everyone, it’s one of those things where you have to decide what’s best for you.”

Leave a reply